Government

Ability to find, afford care is deteriorating in many states

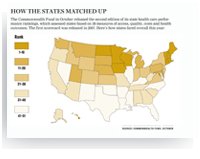

■ A national scorecard again ranked Vermont's health system No. 1 and Mississippi's last, but all states have room to improve.

By Doug Trapp — Posted Oct. 19, 2009

- WITH THIS STORY:

- » Key results of the study

- » Related content

Although preventive care and quality of care has improved in many areas over the last several years, overall patient access to health care and its affordability for some populations declined and still varies dramatically from state to state, according to a new study.

Vermont, Hawaii and Iowa were among the states ranking highest for care access, prevention and treatment, avoidance of unnecessary hospitalizations, health care equity, and health status of the general population, according to "Aiming Higher: Results from a State Scorecard on Health System Performance," released by the Commonwealth Fund on Oct. 8. Mississippi and Oklahoma stood at the bottom of the ranking.

The report -- an update of a 2007 analysis -- found that states' overall rankings did not change dramatically, though some states improved on several of the 38 measures that made up the five main ranking criteria. The indicators in the two reports are based on data collected as early as 1999 and as late as 2007.

"If all states could do as well as the best states, we would have about half the number of uninsured, we would have about 9 million more people getting preventive care and many more people having a chance for a healthy life," said Karen Davis, PhD, the Commonwealth Fund's president.

Although fewer children lost health insurance coverage since the 2007 scorecard, more adults became uninsured. The number of states with childhood uninsured rates of 16% or more declined from nine to three between the two reports. The number of states with nonelderly adult uninsured rates of 23% or more increased from two to nine.

Gaps in equity grew in many states. Those measures reflect the difference in health care experiences for the public based on income level, health insurance status, and race and ethnicity. For example, the percentage of adults who needed to visit a doctor in the last year but did not do so because of cost increased in 25 states. The analysis does not reflect the latest economic recession's impact.

Still, states made gains in the areas of preventive care and treatment quality, with hospitals and nursing homes leading the way. Twenty-two percent more patients on average received appropriate care to prevent surgical complications, representing improvement across every state except one and bringing the national average to 84.6%. Also, 47 states decreased their percentage of high-risk long-term nursing home patients with pressure ulcers.

The report again ranked Mississippi at No. 51 among the 50 states and the District of Columbia, a ranking that's probably accurate, said Randy Easterling, MD, president of the Mississippi State Medical Assn. and a family physician. The state achieved no rank higher than 45 for any of the five major criteria.

Dr. Easterling said poverty in the Mississippi Delta is a huge obstacle, as is the state's high obesity rate. "On every national survey that's done, we've been the fattest state in the country for the last five or six years."

The state's Medicaid program pays physicians at 90% of Medicare rates, which encourages doctors to participate, Dr. Easterling said. But financial and cultural barriers lead many Mississippians to avoid seeking health care.

Sometimes people can't go because they don't have a car or gas money. Sometimes they aren't in the habit of seeing a doctor, Dr. Easterling said. "The health care is there, but getting people to access it is a real challenge."

Oklahoma ranked No. 49 in the survey and also had low rankings in each of the report's five main categories. Wes Glinsmann, the Oklahoma State Medical Assn.'s director of state legislative and political affairs, said state leaders realize the status quo is not acceptable when it comes to the state's high rate of smoking, obesity and chronic disease. "We're starting to open our eyes to some of the larger problems."

On the positive side

The Commonwealth Fund's report ranked Vermont No. 1 overall. It ranked second on measures of equity and third for prevention and treatment quality.

"It's really been a 25- or 30-year effort to improve our health care system," said Paul Harrington, the Vermont Medical Society's executive vice president. He said the process started with reforms in the early 1990s requiring health insurers to offer individual health plans to all.

More recently, the state's Catamount Health Plan -- adopted in 2006 -- offers coverage to the uninsured, and its Children's Health Insurance Program covers kids in families earning up to 300% of the federal poverty level.

Still, Vermont has about 60,000 people without health insurance, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates, which led to the state ranking only No. 13 on access in the Commonwealth Fund scorecard.

Vermont Gov. Jim Douglas credited the state's Blueprint for Health with improving its system of health care. The program aims to improve the quality and coordination of chronic care delivery through medical homes and a statewide health information network.

Hawaii came in second overall, and second for the ability of its residents to live healthy lives. April Donahue, executive director of the Hawaii Medical Assn., said the state's predominant Asian population typically has a healthy diet.

Since the 1970s, Hawaii has required most employers to offer health insurance to employees who work 20 or more hours a week. "We can pat ourselves on the back for some of it," Donahue said.

But she lamented the lack of access to health care for people who live on some outer islands, a situation partly driven by physician shortages in those places.

Other aspects of Hawaii's health system could use improvement, the report found. For example, the state ranked No. 16 on prevention and treatment.