profession

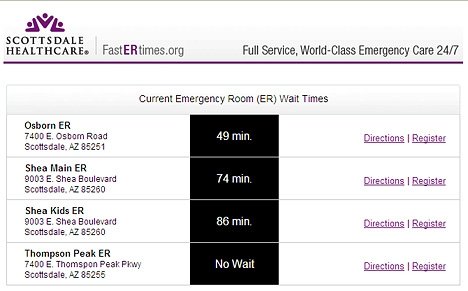

Scottsdale Healthcare in Arizona began posting online the wait times at its four emergency departments in April 2008. Its patient satisfaction scores have improved by 2 percentage points since then. Screen capture from http://www.fastertimes.org/

Posting emergency wait times: Good marketing or good medicine?

■ Hospitals see an opportunity to boost revenue, but doctors say the growing trend could discourage patients from seeking appropriate care.

By Kevin B. O’Reilly — Posted Oct. 11, 2010

- WITH THIS STORY:

- » External links

- » Related content

Every three minutes, Scottsdale Healthcare in Arizona tells patients how long they can expect to wait to see a doctor or other health professional at one of its four emergency departments. The times are automatically posted on electronic billboard ads and the hospital system's website.

Posting ED wait times on billboards, websites, Twitter accounts and mobile apps may seem like a way to better serve patients. Yet it could backfire, some physicians say.

Hospital systems from Oregon to Arizona to Virginia see it as an opportunity to boost revenue and smooth patient demand over the course of the day and week, as well as among different EDs they operate. The argument is also made that greater transparency about wait times could encourage hospital administrators to devote more resources to reducing patient boarding and diversion.

But the growing trend could lead to misuse. Patients could self-triage in a dangerous way. There could be inappropriate use of the emergency department. There also might be a misplaced emphasis on door-to-doctor times versus more meaningful measures, such as how long it takes for an ED patient to be admitted or discharged once their care is completed.

"The most significant risk deals with patient safety," said Jay Kaplan, MD, a member of the American College of Emergency Physicians' board of directors. "I can imagine a patient with chest discomfort or pain going on the Internet and finding that the hospital closest to him has a 40-minute wait, and a hospital that is 15 minutes farther away has a three-minute wait, and deciding to drive across town to that other hospital and suffering a heart attack during the trip."

Another concern is that posted wait times would discourage patients from seeking emergency care because they are unaware that life-threatening conditions are treated immediately, said Dino Rumoro, DO, chair of the Dept. of Emergency Medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Rush does not post its wait times, which have averaged 50 minutes since a nearby hospital closed.

"What about that patient who says, 'I'm not really sure it's my heart,' and then they stay home and die?" Dr. Rumoro asked. "How do you measure that? You would have to somehow document the people who didn't show up because the wait was too long."

If hospitals begin to compete on this and other wait measures, patient care could be compromised, Dr. Rumoro said.

"If you want to just pit a couple of emergency departments against each other and see who has the fastest throughput times, well, you just bypass the ordering of any tests," he said. "I can get you a throughput time of 10 minutes and you're out the door -- here's my assessment based on a physical exam only."

No study of practice

The hospitals publicly posting their waits appear to be seeing patients quickly, with times often listed as less than half an hour. However, no peer-reviewed medical study has examined the effects of the practice on patient outcomes, experts said.

Scottsdale Healthcare began posting wait times in April 2008 at its four EDs, all of which are within about 15 minutes' driving time of one another in the city (two -- a general ED and a pediatrics ED -- are housed at the same center). Its patient satisfaction scores have improved by 2 percentage points, said Nancy Hicks-Arsenault, RN, the organization's systems director of emergency services.

"Our philosophy is that we want patients to seek care when they need it and provide that care as soon as possible to them," she said. "We want them to have a choice in where they get that care."

Before the hospital's four EDs started posting wait times, which reflect the most recent patient's experience, patients waited the longest at Scottsdale Healthcare Medical Center Osborn, a Level I trauma center and stroke center. Now patients are more evenly distributed among the system's EDs.

Hicks-Arsenault acknowledged the potential danger of patients being scared off by long wait times.

"It's hard for the general public to know what's an emergency and what is not," she said. "Chest pain isn't always a heart attack, but it can be. We don't want the public to make those choices and have a bad outcome."

She said patients in Scottsdale are well-educated about when to use the emergency department appropriately, and there is little reason to think more patients are misusing Scottsdale's EDs for care that should be provided in physician offices or urgent-care centers. The patient population being served in the organization's EDs has a similar level of acuity as before the wait-time postings began, Hicks-Arsenault said.

A revenue opportunity

Publicly posting wait times can be a good business move for hospitals, said Arthur L. Kellermann, MD, MPH, director of the Public Health Systems and Preparedness Initiative at the Arlington, Va., office of the nonprofit think tank RAND Corp.

"Clearly, what's going on is that hospitals are competing for paying customers," Dr. Kellermann said. "There's a realization that, nationally, more than half of all admissions to the hospital are coming through the emergency department now. In markets that have many people with substantial levels of health insurance coverage, that's a major source of revenue for hospitals."

Hospital administrators' attitudes toward emergency patients is changing, said Leora I. Horwitz, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Yale University School of Medicine in Connecticut.

"Hospitals used to make their emergency departments too small to discourage people from coming," said Dr. Horwitz, who has published research on hospitals' performance on wait times. "ER patients are not seen as loss leaders anymore."

Dr. Kellermann said transparency about how long it takes to be seen by a doctor or other health professional in the ED is a positive development. But he added that hospitals should disclose other quality information, such as an ED's occupancy rate, how long it takes to reach an inpatient bed if admitted, the number of hours the ED is on diversion due to crowding and which specialists are available on-call.

"Then you'll see hospitals focusing much more directly on access, patient flow and ambulance diversion," he said. "As long as they're out of sight, they will be out of mind and won't be addressed."

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is considering requiring hospitals publicly to report their performance on how long it takes for emergency patients to be admitted to a hospital bed or discharged from the ED or they could lose 2% in their annual Medicare pay increase. Median wait times are among the measures that hospitals can use to satisfy the "meaningful use" requirements for electronic health records.

The EDs that publicly post wait times show that physicians and hospitals have some control over how quickly they move patients from the door to the emergency treatment bay, up to the floor and back home, Dr. Horwitz said. She co-wrote a February Annals of Emergency Medicine study of more than 35,000 patient visits to 364 hospital EDs that found that only 31% of EDs achieved the nationally recommended triage time -- less than an hour to be treated by a physician -- for more than 90% of their patients.

"People have been a little fatalistic about this," she said. "But some hospitals do better than others, and what all of these things -- the public reporting, the Twittering, the quality measures -- are doing is bringing it home to all hospitals to look at your individual performance and know that you can do better."